Peter Rost, M.D., is a former Pfizer Marketing Vice President providing services as a medical device and drug expert witness and pharmaceutical marketing expert. Judge Sanders: "The court agrees with defendants' view that Dr. Rost is a very adept and seasoned expert witness." He is also the author of Emergency Surgery, The Whistleblower and Killer Drug. You can reach him on rostpeter (insert symbol) hotmail.com. Follow on https://twitter.com/peterrost

Friday, October 30, 2009

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Monday, October 26, 2009

Friday, October 23, 2009

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Monday, October 19, 2009

Friday, October 16, 2009

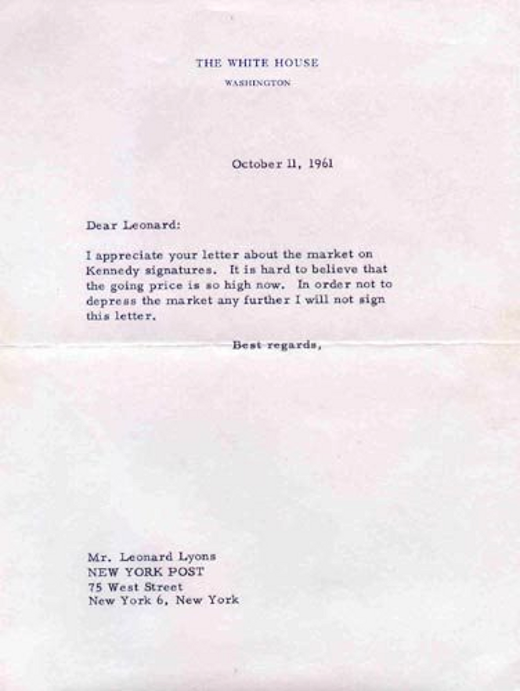

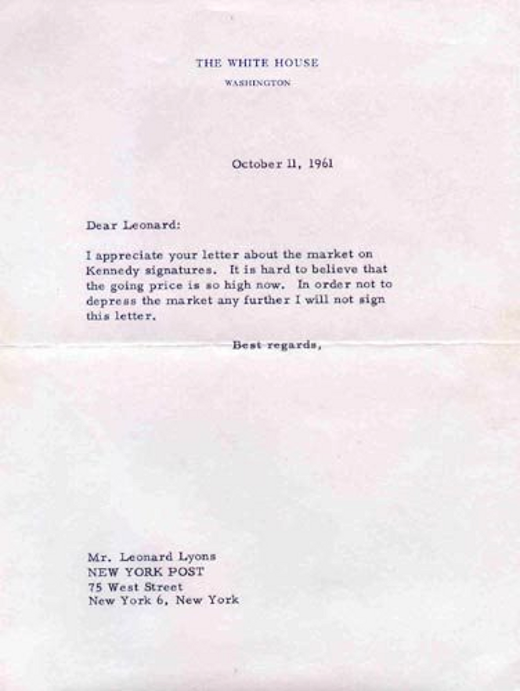

I will not sign this letter

In 1961, New York Post columnist Leonard Lyons contacted John F. Kennedy after seeing Presidential autographs for sale in a store. At the time, George Washington’s was priced at $175, Ulysses S. Grant's at $55, Franklin D. Roosevelt's at $75, Teddy Roosevelt’s at $67.50, and JFK’s at $75. Below is the response mailed to Lyons.

For more amazing letters go to Letters of Note.

Letters of Note is an attempt to gather and sort fascinating letters, postcards, telegrams, faxes, and memos. Scans/photos where possible. Fakes will be sneered at. Updated 2-3 times every weekday.

For more amazing letters go to Letters of Note.

Letters of Note is an attempt to gather and sort fascinating letters, postcards, telegrams, faxes, and memos. Scans/photos where possible. Fakes will be sneered at. Updated 2-3 times every weekday.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

6-year-old Colorado boy floats away in balloon.

A 6-year-old boy in northern Colorado climbed into a hot-air balloon aircraft and floated away today, forcing officials to scramble to figure out how to rescue the boy. Balloon can fly as high as 10,0000 ft. I guess every American will watch television news tonight. No conclusion yet. Turn on CNN or FOX and watch live.

Monday, October 12, 2009

A Canadian doctor diagnoses U.S. healthcare

The caricature of 'socialized medicine' is used by corporate interests to confuse Americans and maintain their bottom lines instead of patients' health.

By Michael M. Rachlis

Universal health insurance is on the American policy agenda for the fifth time since World War II. In the 1960s, the U.S. chose public coverage for only the elderly and the very poor, while Canada opted for a universal program for hospitals and physicians' services. As a policy analyst, I know there are lessons to be learned from studying the effect of different approaches in similar jurisdictions. But, as a Canadian with lots of American friends and relatives, I am saddened that Americans seem incapable of learning them.

Our countries are joined at the hip. We peacefully share a continent, a British heritage of representative government and now ownership of GM. And, until 50 years ago, we had similar health systems, healthcare costs and vital statistics.

The U.S.' and Canada's different health insurance decisions make up the world's largest health policy experiment. And the results?

On coverage, all Canadians have insurance for hospital and physician services. There are no deductibles or co-pays. Most provinces also provide coverage for programs for home care, long-term care, pharmaceuticals and durable medical equipment, although there are co-pays.

On the U.S. side, 46 million people have no insurance, millions are underinsured and healthcare bills bankrupt more than 1 million Americans every year.

Lesson No. 1: A single-payer system would eliminate most U.S. coverage problems.

On costs, Canada spends 10% of its economy on healthcare; the U.S. spends 16%. The extra 6% of GDP amounts to more than $800 billion per year. The spending gap between the two nations is almost entirely because of higher overhead. Canadians don't need thousands of actuaries to set premiums or thousands of lawyers to deny care. Even the U.S. Medicare program has 80% to 90% lower administrative costs than private Medicare Advantage policies. And providers and suppliers can't charge as much when they have to deal with a single payer.

Lessons No. 2 and 3: Single-payer systems reduce duplicative administrative costs and can negotiate lower prices.

Because most of the difference in spending is for non-patient care, Canadians actually get more of most services. We see the doctor more often and take more drugs. We even have more lung transplant surgery. We do get less heart surgery, but not so much less that we are any more likely to die of heart attacks. And we now live nearly three years longer, and our infant mortality is 20% lower.

Lesson No. 4: Single-payer plans can deliver the goods because their funding goes to services, not overhead.

The Canadian system does have its problems, and these also provide important lessons. Notwithstanding a few well-publicized and misleading cases, Canadians needing urgent care get immediate treatment. But we do wait too long for much elective care, including appointments with family doctors and specialists and selected surgical procedures. We also do a poor job managing chronic disease.

However, according to the New York-based Commonwealth Fund, both the American and the Canadian systems fare badly in these areas. In fact, an April U.S. Government Accountability Office report noted that U.S. emergency room wait times have increased, and patients who should be seen immediately are now waiting an average of 28 minutes. The GAO has also raised concerns about two- to four-month waiting times for mammograms.

On closer examination, most of these problems have little to do with public insurance or even overall resources. Despite the delays, the GAO said there is enough mammogram capacity.

These problems are largely caused by our shared politico-cultural barriers to quality of care. In 19th century North America, doctors waged a campaign against quacks and snake-oil salesmen and attained a legislative monopoly on medical practice. In return, they promised to set and enforce standards of practice. By and large, it didn't happen. And perverse incentives like fee-for-service make things even worse.

Using techniques like those championed by the Boston-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement, providers can eliminate most delays. In Hamilton, Ontario, 17 psychiatrists have linked up with 100 family doctors and 80 social workers to offer some of the world's best access to mental health services. And in Toronto, simple process improvements mean you can now get your hip assessed in one week and get a new one, if you need it, within a month.

Lesson No. 5: Canadian healthcare delivery problems have nothing to do with our single-payer system and can be fixed by re-engineering for quality.

U.S. health policy would be miles ahead if policymakers could learn these lessons. But they seem less interested in Canada's, or any other nation's, experience than ever. Why?

American democracy runs on money. Pharmaceutical and insurance companies have the fuel. Analysts see hundreds of billions of premiums wasted on overhead that could fund care for the uninsured. But industry executives and shareholders see bonuses and dividends.

Compounding the confusion is traditional American ignorance of what happens north of the border, which makes it easy to mislead people. Boilerplate anti-government rhetoric does the same. The U.S. media, legislators and even presidents have claimed that our "socialized" system doesn't let us choose our own doctors. In fact, Canadians have free choice of physicians. It's Americans these days who are restricted to "in-plan" doctors.

Unfortunately, many Americans won't get to hear the straight goods because vested interests are promoting a caricature of the Canadian experience.

Michael M. Rachlis is a physician, health policy analyst and author in Toronto.

By Michael M. Rachlis

Universal health insurance is on the American policy agenda for the fifth time since World War II. In the 1960s, the U.S. chose public coverage for only the elderly and the very poor, while Canada opted for a universal program for hospitals and physicians' services. As a policy analyst, I know there are lessons to be learned from studying the effect of different approaches in similar jurisdictions. But, as a Canadian with lots of American friends and relatives, I am saddened that Americans seem incapable of learning them.

Our countries are joined at the hip. We peacefully share a continent, a British heritage of representative government and now ownership of GM. And, until 50 years ago, we had similar health systems, healthcare costs and vital statistics.

The U.S.' and Canada's different health insurance decisions make up the world's largest health policy experiment. And the results?

On coverage, all Canadians have insurance for hospital and physician services. There are no deductibles or co-pays. Most provinces also provide coverage for programs for home care, long-term care, pharmaceuticals and durable medical equipment, although there are co-pays.

On the U.S. side, 46 million people have no insurance, millions are underinsured and healthcare bills bankrupt more than 1 million Americans every year.

Lesson No. 1: A single-payer system would eliminate most U.S. coverage problems.

On costs, Canada spends 10% of its economy on healthcare; the U.S. spends 16%. The extra 6% of GDP amounts to more than $800 billion per year. The spending gap between the two nations is almost entirely because of higher overhead. Canadians don't need thousands of actuaries to set premiums or thousands of lawyers to deny care. Even the U.S. Medicare program has 80% to 90% lower administrative costs than private Medicare Advantage policies. And providers and suppliers can't charge as much when they have to deal with a single payer.

Lessons No. 2 and 3: Single-payer systems reduce duplicative administrative costs and can negotiate lower prices.

Because most of the difference in spending is for non-patient care, Canadians actually get more of most services. We see the doctor more often and take more drugs. We even have more lung transplant surgery. We do get less heart surgery, but not so much less that we are any more likely to die of heart attacks. And we now live nearly three years longer, and our infant mortality is 20% lower.

Lesson No. 4: Single-payer plans can deliver the goods because their funding goes to services, not overhead.

The Canadian system does have its problems, and these also provide important lessons. Notwithstanding a few well-publicized and misleading cases, Canadians needing urgent care get immediate treatment. But we do wait too long for much elective care, including appointments with family doctors and specialists and selected surgical procedures. We also do a poor job managing chronic disease.

However, according to the New York-based Commonwealth Fund, both the American and the Canadian systems fare badly in these areas. In fact, an April U.S. Government Accountability Office report noted that U.S. emergency room wait times have increased, and patients who should be seen immediately are now waiting an average of 28 minutes. The GAO has also raised concerns about two- to four-month waiting times for mammograms.

On closer examination, most of these problems have little to do with public insurance or even overall resources. Despite the delays, the GAO said there is enough mammogram capacity.

These problems are largely caused by our shared politico-cultural barriers to quality of care. In 19th century North America, doctors waged a campaign against quacks and snake-oil salesmen and attained a legislative monopoly on medical practice. In return, they promised to set and enforce standards of practice. By and large, it didn't happen. And perverse incentives like fee-for-service make things even worse.

Using techniques like those championed by the Boston-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement, providers can eliminate most delays. In Hamilton, Ontario, 17 psychiatrists have linked up with 100 family doctors and 80 social workers to offer some of the world's best access to mental health services. And in Toronto, simple process improvements mean you can now get your hip assessed in one week and get a new one, if you need it, within a month.

Lesson No. 5: Canadian healthcare delivery problems have nothing to do with our single-payer system and can be fixed by re-engineering for quality.

U.S. health policy would be miles ahead if policymakers could learn these lessons. But they seem less interested in Canada's, or any other nation's, experience than ever. Why?

American democracy runs on money. Pharmaceutical and insurance companies have the fuel. Analysts see hundreds of billions of premiums wasted on overhead that could fund care for the uninsured. But industry executives and shareholders see bonuses and dividends.

Compounding the confusion is traditional American ignorance of what happens north of the border, which makes it easy to mislead people. Boilerplate anti-government rhetoric does the same. The U.S. media, legislators and even presidents have claimed that our "socialized" system doesn't let us choose our own doctors. In fact, Canadians have free choice of physicians. It's Americans these days who are restricted to "in-plan" doctors.

Unfortunately, many Americans won't get to hear the straight goods because vested interests are promoting a caricature of the Canadian experience.

Michael M. Rachlis is a physician, health policy analyst and author in Toronto.

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Friday, October 09, 2009

Obama won the Nobel Price for Peace?!

He hasn't been in office for more than six months . . . !

Two key White House aides were both convinced they were being punked when they heard the news, reported ABC News' George Stephanopoulos.

"It's not April 1, is it?" one said.

As for the impact on U.S. politics . . . it can only be for the better, so congratulations Mr. President!

Two key White House aides were both convinced they were being punked when they heard the news, reported ABC News' George Stephanopoulos.

"It's not April 1, is it?" one said.

As for the impact on U.S. politics . . . it can only be for the better, so congratulations Mr. President!

Thursday, October 08, 2009

Wednesday, October 07, 2009

Daddy, don't go!

When Army Reservist Staff Sgt. Brett Bennethum lined up in formation at his deployment to Iraq this July, his daughter wouldn't let go.

Tuesday, October 06, 2009

Lars Bildman, former Astra CEO, known for his love of sexy sales reps, wild parties and crazy clothes, must return $7 million in pay.

Some people claim a book is being written about his story, and former reps and employees have been going on about him, telling memories right here for the last few years.

There is hate and love (a bit too much love according to some) and very little in between, just like any Shakespearean drama.

It all started with a story in BusinessWeek, later he was arrested by federal authorities and charged with 35 counts, including fraud and tax evasion. Astra sued him, claiming he sexually harassed and intimidated employees, destroyed documents and records, and concocted "tales of conspiracy involving ex-KGB agents and competitors...in a last-ditch effort to distract attention from the real wrongdoer; Bildman himself." The suit also said he used company funds to rent yachts and pay for prostitutes.

Bildman plead guilty to failing to report over $1 million in income and agreed to serve 21 months in a federal prison. He also had to pay the government more than $ 300,000 in back taxes and interest.

Massachusetts’ highest court yesterday ruled that the former chief executive of Westborough pharmaceutical company Astra USA Inc. must forfeit nearly $7 million in salary and bonuses he collected from 1991 through 1996, when he was fired for harassing female employees and misappropriating company funds.

Reversing the decision of a lower court judge, who ruled Astra could not recover compensation paid to Lars Bildman, the Supreme Judicial Court opinion cited the law of New York state, where Astra was incorporated, pertaining to corporate officers who breach their fiduciary duty.

In a 21-page decision, the state’s high court justices said New York’s “faithless servant’’ doctrine allows the company to go after $5.6 million in salary and $1.2 million in bonuses paid to Bildman.

The decision upheld Suffolk Superior Court Judge Margaret Hinkle on several other issues in the long-running litigation, but its reversal on the forfeiture question appeared to close the curtain on the high-profile sexual harassment and embezzlement case.

Company attorney Jeff Robbins, a partner at Boston law firm Mintz Levin, hailed the high court’s decision to force Bildman to forfeit his compensation. Robbins said the ruling was not only important in Massachusetts and New York, but could set a national precedent if other states embrace New York’s forfeiture standard.

“Given the prominence of this case and given the forcefulness of the court’s ruling, this is a holding that could have national significance in the area of forfeiture law,’’ he said.

Robbins represented Astra’s successor company - drug maker AstraZeneca, based in England - before the Supreme Judicial Court. AstraZeneca was formed through a 1999 merger between Britain’s Zeneca Group PLC and Sweden’s Astra AB, the parent of Astra USA.

Corporate boards face mounting pressure to crack down on executives who breach their fiduciary duty, said Thomas C. Kohler, a Boston College law professor. He said courts are likely to see more cases of companies trying to recoup compensation from wrongdoers.

“This is going to become an issue of greater and greater import,’’ Kohler said. “This decision in Massachusetts may give other courts a framework for ruling on similar kinds of cases. But what one state does is not necessarily of pressing interest to other states.’’

At the US office of AstraZeneca in Wilmington, Del., spokeswoman Laura Woodin said the court ruling “validates the actions of Astra USA to hold its former executive accountable for his conduct and allows our company to move forward.’’

Bildman, the Swedish-born executive at the center of the case, yesterday said he is retired and living in Vermont on Social Security. He said his wife divorced him as a result of the case and that he has spent nearly all the money he earned defending himself in court.

“Of course I am disappointed,’’ Bildman said. “It would be impossible not to be disappointed. The money doesn’t concern me at all. I have no money, so it will be uncollectable.’’

Michael D. Weisman, attorney for Bildman, said he could not discuss the ruling in detail until he had conferred with his client. But he noted that the court upheld lower court rulings that awarded Bildman about $200,000 in damages in connection with a stock grant, prevented Astra from rescinding an employment agreement with him, and held that his client did not have to pay the costs of Astra’s investigation.

“I’m grateful that the court reaffirmed many of the important issues in which Bildman prevailed in the court below,’’ said Weisman, a partner at the Boston law firm of Weisman & McIntyre.

Bildman was fired in 1996 after an internal investigation found he and other managers harassed female employees at Astra in Westborough and that he spent company money on home repairs, vacations, and high-priced prostitutes. Women at the company said Bildman engaged in “up-close and personal conduct’’ and they were under relentless pressure to dress provocatively and to socialize with Bildman and other executives to ensure their employment. The allegations were first reported in BusinessWeek magazine.

In 1997, a federal grant jury sitting in Massachusetts indicted Bildman on multiple counts. He ultimately pleaded guilty to falsifying tax returns and served an 18-month prison sentence.

Astra, meanwhile, agreed in 1998 to pay $9.8 million to settle charges brought by the US government, in what then was the largest sexual harassment case in the history of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Separately in 1998, the company sued Bildman in superior court for misuse of funds, fraud, and breach of fiduciary duty, while he countersued Astra for wrongful termination.

A jury ruled against Bildman on 24 of 25 counts in 2002. He appealed, setting up yesterday’s decision.

There is hate and love (a bit too much love according to some) and very little in between, just like any Shakespearean drama.

It all started with a story in BusinessWeek, later he was arrested by federal authorities and charged with 35 counts, including fraud and tax evasion. Astra sued him, claiming he sexually harassed and intimidated employees, destroyed documents and records, and concocted "tales of conspiracy involving ex-KGB agents and competitors...in a last-ditch effort to distract attention from the real wrongdoer; Bildman himself." The suit also said he used company funds to rent yachts and pay for prostitutes.

Bildman plead guilty to failing to report over $1 million in income and agreed to serve 21 months in a federal prison. He also had to pay the government more than $ 300,000 in back taxes and interest.

Massachusetts’ highest court yesterday ruled that the former chief executive of Westborough pharmaceutical company Astra USA Inc. must forfeit nearly $7 million in salary and bonuses he collected from 1991 through 1996, when he was fired for harassing female employees and misappropriating company funds.

Reversing the decision of a lower court judge, who ruled Astra could not recover compensation paid to Lars Bildman, the Supreme Judicial Court opinion cited the law of New York state, where Astra was incorporated, pertaining to corporate officers who breach their fiduciary duty.

In a 21-page decision, the state’s high court justices said New York’s “faithless servant’’ doctrine allows the company to go after $5.6 million in salary and $1.2 million in bonuses paid to Bildman.

The decision upheld Suffolk Superior Court Judge Margaret Hinkle on several other issues in the long-running litigation, but its reversal on the forfeiture question appeared to close the curtain on the high-profile sexual harassment and embezzlement case.

Company attorney Jeff Robbins, a partner at Boston law firm Mintz Levin, hailed the high court’s decision to force Bildman to forfeit his compensation. Robbins said the ruling was not only important in Massachusetts and New York, but could set a national precedent if other states embrace New York’s forfeiture standard.

“Given the prominence of this case and given the forcefulness of the court’s ruling, this is a holding that could have national significance in the area of forfeiture law,’’ he said.

Robbins represented Astra’s successor company - drug maker AstraZeneca, based in England - before the Supreme Judicial Court. AstraZeneca was formed through a 1999 merger between Britain’s Zeneca Group PLC and Sweden’s Astra AB, the parent of Astra USA.

Corporate boards face mounting pressure to crack down on executives who breach their fiduciary duty, said Thomas C. Kohler, a Boston College law professor. He said courts are likely to see more cases of companies trying to recoup compensation from wrongdoers.

“This is going to become an issue of greater and greater import,’’ Kohler said. “This decision in Massachusetts may give other courts a framework for ruling on similar kinds of cases. But what one state does is not necessarily of pressing interest to other states.’’

At the US office of AstraZeneca in Wilmington, Del., spokeswoman Laura Woodin said the court ruling “validates the actions of Astra USA to hold its former executive accountable for his conduct and allows our company to move forward.’’

Bildman, the Swedish-born executive at the center of the case, yesterday said he is retired and living in Vermont on Social Security. He said his wife divorced him as a result of the case and that he has spent nearly all the money he earned defending himself in court.

“Of course I am disappointed,’’ Bildman said. “It would be impossible not to be disappointed. The money doesn’t concern me at all. I have no money, so it will be uncollectable.’’

Michael D. Weisman, attorney for Bildman, said he could not discuss the ruling in detail until he had conferred with his client. But he noted that the court upheld lower court rulings that awarded Bildman about $200,000 in damages in connection with a stock grant, prevented Astra from rescinding an employment agreement with him, and held that his client did not have to pay the costs of Astra’s investigation.

“I’m grateful that the court reaffirmed many of the important issues in which Bildman prevailed in the court below,’’ said Weisman, a partner at the Boston law firm of Weisman & McIntyre.

Bildman was fired in 1996 after an internal investigation found he and other managers harassed female employees at Astra in Westborough and that he spent company money on home repairs, vacations, and high-priced prostitutes. Women at the company said Bildman engaged in “up-close and personal conduct’’ and they were under relentless pressure to dress provocatively and to socialize with Bildman and other executives to ensure their employment. The allegations were first reported in BusinessWeek magazine.

In 1997, a federal grant jury sitting in Massachusetts indicted Bildman on multiple counts. He ultimately pleaded guilty to falsifying tax returns and served an 18-month prison sentence.

Astra, meanwhile, agreed in 1998 to pay $9.8 million to settle charges brought by the US government, in what then was the largest sexual harassment case in the history of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Separately in 1998, the company sued Bildman in superior court for misuse of funds, fraud, and breach of fiduciary duty, while he countersued Astra for wrongful termination.

A jury ruled against Bildman on 24 of 25 counts in 2002. He appealed, setting up yesterday’s decision.

Monday, October 05, 2009

Seven rules for successful negotiations

1. Understand who you negotiate with. Call it empathy. There’s no substitute for understanding the other side of the negotiation. What do they really want?

2. Find the win-win. Either both parties lose or both parties win. Find out what they need to win and you may win as well. So look for that in every negotiation.

3. Everything is negotiable. Don’t narrow a negotiation down to just one issue. Develop as many negotiable deal points as may apply and give the other party options.

4. Be honest and fair. One uncovered lie will destroy the negotiation. You may not like the other party, but there must be trust to complete a negotiation.

5. Use the power of competition. What are your alternative options if you don’t reach a deal and how will that affect you and the other party?

6. Humans don’t appreciate what they don’t have to fight for. The longer the negotiation, the more each party have invested in finding a solution.

7. Be prepared to walk away. If you are wedded to the thought of reaching a deal you will lose. Prepare an exit strategy.

2. Find the win-win. Either both parties lose or both parties win. Find out what they need to win and you may win as well. So look for that in every negotiation.

3. Everything is negotiable. Don’t narrow a negotiation down to just one issue. Develop as many negotiable deal points as may apply and give the other party options.

4. Be honest and fair. One uncovered lie will destroy the negotiation. You may not like the other party, but there must be trust to complete a negotiation.

5. Use the power of competition. What are your alternative options if you don’t reach a deal and how will that affect you and the other party?

6. Humans don’t appreciate what they don’t have to fight for. The longer the negotiation, the more each party have invested in finding a solution.

7. Be prepared to walk away. If you are wedded to the thought of reaching a deal you will lose. Prepare an exit strategy.

Friday, October 02, 2009

Notice anything in this wedding picture that didn't exist ten years ago?

Hint: Check out the priest.

Would you send your children to school if "only 5%" of teachers were involved in child sex abuse?

Quote of the day from the Catholic Church:

The statement, read out by Archbishop Silvano Tomasi, the Vatican's permanent observer to the UN, defended its record by claiming that "available research" showed that only 1.5%-5% of Catholic clergy were involved in child sex abuse.

The statement, read out by Archbishop Silvano Tomasi, the Vatican's permanent observer to the UN, defended its record by claiming that "available research" showed that only 1.5%-5% of Catholic clergy were involved in child sex abuse.

Health Care in London

9/9/2009 By Thomas P. Beresford, MD

I was in London four weeks ago when around 11 p.m., I felt a sharp pain. I feel for a point on my body - a third of the distance from the right hip bone to the belly button. Pressing ever so lightly, the right side of my belly lights up with pain as though on fire. I can not stand.

Using what I call a cell and the British call a mobile, I phone the night manager, who then calls the paramedics. With an IV line and morphine in the ambulance, they take me to St. Mary's Hospital Paddington. "Is that hospital any good," I ask. "Oh yes," he says. "And don't worry, the Accident and Emergency visit is free."

An Irish nurse tends to me, watching my vital signs and the pain. Then comes an emergency service doctor and then a junior followed by a mid-level surgeon - what we call residents. I received chest and abdomen X-rays and then a CT scan of the belly.

I was admitted to a surgical ward in the early hours. "We don't want to operate on your appendix in the middle of the night," my doctors told me. "We want you to see the Specialist Registrar who is the most practiced at laparoscopic (surgery through a tube) work through the belly button."

I meet him the next afternoon. He has the self confidence of his profession. "I am what you might call the 'Chief Resident' in your system." I grin.

"I was one of those myself but in psychiatry," I tell him. Eye to eye, we exchange knowing and assertive glances, one Chief to another.

I go under and wake six hours later on the ward wearing an oxygen mask, a dressing over my belly button and a drain stitched in lower down. As I clear, I begin to try deep breathing to keep my lungs clean. The fire is gone. There is soreness, but I can cough.

The nurse tells me it's too early to walk. I'm on IV fluids and antibiotics with less pain killer but enough to cover. The next day I don't need any. The first night I drift in and out of sleep as my water output returns.

At 3 a.m. another junior surgeon and a student wake me to be sure the repair does not leak. I have no pain, and none when she gently tests the right side of my belly.

The team and the mid-level resident see me the next morning. "You had a nasty appendix," the team tells me. "The tissue was dead and leaking into the abdomen. The surgery usually takes twenty minutes. Yours took ninety. They were surprised you could walk to the anesthesia suite."

The Specialist Registrar stops by in mid-afternoon and says, "I was worried. We've watched you closely and will for a few more days. But the worst is over." Then he grins and says eye-to-eye "You're a tough man." I said, "Thanks."

I went back to the hotel two days later, pain free, walking, able to shower, then to sleep, and easing back into an appetite.

I've been a physician and a professor in American medical schools for nearly 40 years. I've heard all the arguments against universal coverage and all the stale criticisms of the National Health Service. When I tell a friend about the NHS, fresh off my surgery in Britain, she says "I've been paying lots of good money for health insurance for years."

"And what have you got to show for it besides the receipts?" I ask her.

Look what we all could have for far less than it costs to fund insurance companies and malpractice lawyers. Health care for everyone. If Britain can do it, the U.S. certainly can.

Thomas P. Beresford, MD, is a professor of Psychiatry at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and School of Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver.

I was in London four weeks ago when around 11 p.m., I felt a sharp pain. I feel for a point on my body - a third of the distance from the right hip bone to the belly button. Pressing ever so lightly, the right side of my belly lights up with pain as though on fire. I can not stand.

Using what I call a cell and the British call a mobile, I phone the night manager, who then calls the paramedics. With an IV line and morphine in the ambulance, they take me to St. Mary's Hospital Paddington. "Is that hospital any good," I ask. "Oh yes," he says. "And don't worry, the Accident and Emergency visit is free."

An Irish nurse tends to me, watching my vital signs and the pain. Then comes an emergency service doctor and then a junior followed by a mid-level surgeon - what we call residents. I received chest and abdomen X-rays and then a CT scan of the belly.

I was admitted to a surgical ward in the early hours. "We don't want to operate on your appendix in the middle of the night," my doctors told me. "We want you to see the Specialist Registrar who is the most practiced at laparoscopic (surgery through a tube) work through the belly button."

I meet him the next afternoon. He has the self confidence of his profession. "I am what you might call the 'Chief Resident' in your system." I grin.

"I was one of those myself but in psychiatry," I tell him. Eye to eye, we exchange knowing and assertive glances, one Chief to another.

I go under and wake six hours later on the ward wearing an oxygen mask, a dressing over my belly button and a drain stitched in lower down. As I clear, I begin to try deep breathing to keep my lungs clean. The fire is gone. There is soreness, but I can cough.

The nurse tells me it's too early to walk. I'm on IV fluids and antibiotics with less pain killer but enough to cover. The next day I don't need any. The first night I drift in and out of sleep as my water output returns.

At 3 a.m. another junior surgeon and a student wake me to be sure the repair does not leak. I have no pain, and none when she gently tests the right side of my belly.

The team and the mid-level resident see me the next morning. "You had a nasty appendix," the team tells me. "The tissue was dead and leaking into the abdomen. The surgery usually takes twenty minutes. Yours took ninety. They were surprised you could walk to the anesthesia suite."

The Specialist Registrar stops by in mid-afternoon and says, "I was worried. We've watched you closely and will for a few more days. But the worst is over." Then he grins and says eye-to-eye "You're a tough man." I said, "Thanks."

I went back to the hotel two days later, pain free, walking, able to shower, then to sleep, and easing back into an appetite.

I've been a physician and a professor in American medical schools for nearly 40 years. I've heard all the arguments against universal coverage and all the stale criticisms of the National Health Service. When I tell a friend about the NHS, fresh off my surgery in Britain, she says "I've been paying lots of good money for health insurance for years."

"And what have you got to show for it besides the receipts?" I ask her.

Look what we all could have for far less than it costs to fund insurance companies and malpractice lawyers. Health care for everyone. If Britain can do it, the U.S. certainly can.

Thomas P. Beresford, MD, is a professor of Psychiatry at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and School of Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver.

Thursday, October 01, 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)